“As associations proliferate, the space for leadership multiplies. And as leadership of each association rotates, the experience proliferates. In this way, America’s great space for leadership development is in associational life.”

–John McKnight

(Note: The following is an abridged version of my essay, “The Value of Associations and Four Strategies for Involving Them,” from the book: Asset-Based Community Engagement in Higher Education, John Hamerlinck and Julie Plaut, editors, Minnesota Campus Compact, 2014. It is based to a great extent, on the work of the extraordinary John McKnight)

Associations are the magnifiers of gifts and capacities of local people. Because they are voluntary, they are also the least expensive strategy for mobilization. The motivation to associate is based on personal priorities. If we know a community’s associations, we know what people really care about. I have heard John McKnight refer to them as the “implementers of care,” because they mobilize people to get together and are a dominant force in any community.

The key to sustainable, democratic community change lies in groups of people who are at the table not because it is their job, but rather because they care too deeply not to be there. If we truly believe, as educators, in reciprocal partnerships, where the community outcome is just as important as the educational outcome, then those partnerships need to figure out how to involve associations.

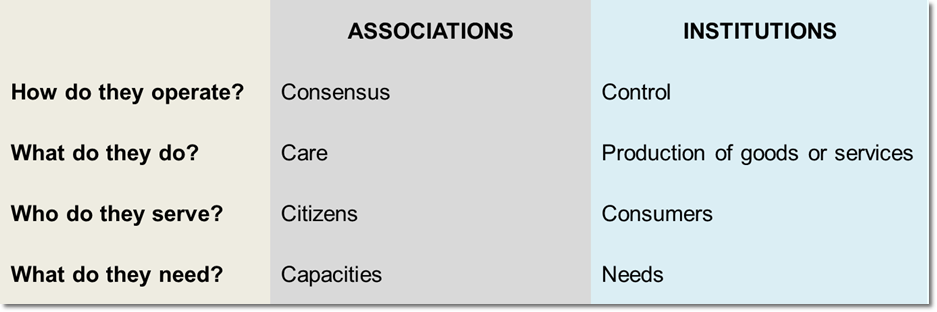

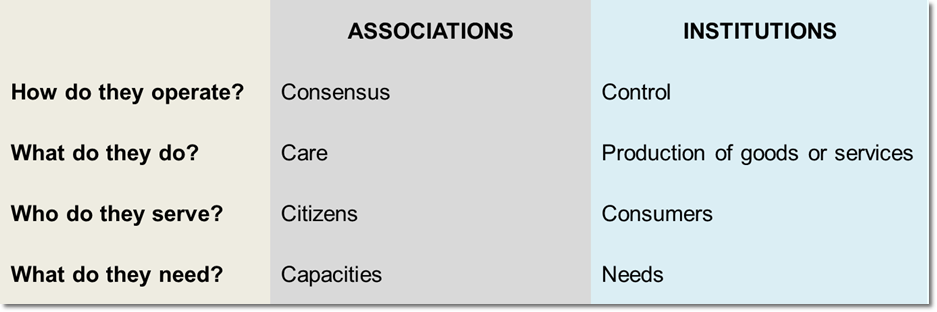

Often we forget that not-for-profit organizations are institutions. They are not led by the people they “serve.” In his piece “The Four-Legged Stool,” McKnight explains some fundamental distinctions between associations and not-for profit corporations:

-

“Associations tend to be informal and horizontal. Not-for-profit corporations are usually formal and hierarchical.

-

Not-for-profits are legally controlled by a few. Associations are activated by the consent of each participant.

-

Associational participants are motivated by diverse incentives other than pay. Not-for-profit employees are provided paid incentives.

-

Associations generally use the experience and knowledge of member citizens to perform their functions. Not-for-profits use the special knowledge of professionals and experts to perform their functions.”

The table below illustrates key distinctions McKnight makes using four important questions as filters. It shows how associations need the capacities of citizens, who care about something, to come to a consensus, and act on their common interests. Institutions, however, need consumers whose needs can be met by consuming goods or services produced under specific controls.

This comparison makes no judgment as to the relative value of either group. The table is simply meant to illustrate the distinct differences between the two types of organizations. Both types of groups are crucial to a democratic society and both must have the noted characteristics in order to work effectively.

It is in these non-elected, non-paid groups who come together for a common purpose where one will find social assets like caring, mutual trust, reciprocity and collective identity. Associations are not always easily identifiable, but they are all around us. Sometimes they have an obvious identity like a book club or quilting group. Other times they are just a group of people who have coffee at the same café three times a week. These groups represent the un-mobilized workforce of community change. They are simply waiting for someone to ask them to act on what they care about.

Four Strategies for Finding and Working with Associations

Mobilizing associations is critically important in ABCD. How might we work with, and support the work of these groups of community members? Here are four places to start.

1. Increase the number of personal relationships in the community.

Whatever your other goals might be, it is always useful to include increasing the number of personal relationships in the community. When people realize that there are others who care deeply about the same things that they do, they start looking for more out there who share their concerns. Pretty soon the talk becomes talk about doing something. Suddenly, a group of concerned residents organize themselves and begin to advocate for change. These associations are at the heart of our democracy.

2. Be deliberate about mapping associational assets.

If you are already committed to addressing a particular issue and your project meetings are only attended by people whose jobs brought them there, then you may not be recognizing the assets of associations. Early on in your planning process, identify community stakeholders and try to identify even a few formal and informal associations to lock arms with in your efforts to improve the community.

Even if these associations don’t immediately seem like they would share your project goals, try anyway. Think of the adopt-a-highway programs all around the country. Most of the student councils, local businesses, and book clubs that volunteer to pick up roadside trash don’t have mission statements about littering or environmental stewardship (if they have mission statements at all). The people in these groups do, however, enjoy the time they spend with people with similar interests; and they enjoy doing things that improve the community’s quality of life—or at least appreciate the public recognition they get on roadside signs. Mapping assets can help find a campus-community partnership version of the adopt-a-highway program.

3. Allow institutions and associations to do the things that they do best.

It is necessary for institutions to produce goods or services under fairly strict controls. When you are on the operating table, you would probably not be comfortable with the surgeon looking for a general consensus by asking: “Where does everybody think I should cut now?” When that surgeon participates in her neighborhood book club, however, nobody expects her to take control by instituting rigid protocols and standards for everyone’s participation.

In 2001, the George W. Bush administration created the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives. After the first round of grants to faith-based organizations revealed that local church groups weren’t necessarily very skilled at federal grant compliance, a subsequent request for proposals included an organizational development component—in other words, it aimed to turn them into institutions. Institutions tend to be good at things like accounting, assessment, and evaluation. Associations are good at things like organizing, caring, compassion, and trust.

Institutions can support associational work by supporting local organizers. They might, for example, serve as the fiscal agent for grants that support the work of people who are passionate about developing their community, but who don’t happen to work for a nonprofit or government entity eligible to receive certain types of grant funding. They might increase the amount of purchasing they do from small, locally-owned businesses. They might make more of their community-based research, community-based participatory research. Imagine ways to complement the work of associations, without taking it over.

4. Provide opportunities for residents’ voices to be heard.

There are countless ways to find a community’s associations. There are the usual lists that folks at a Chamber of Commerce or a Welcome Wagon might have, but there are also types of civic engagement that can help unearth the often invisible groups in a community. Citizen journalism, oral history, and community arts projects are just a few of the ways to listen to residents, and to have them lead you to associations you may not know about. Many community associations may be active in online spaces. Do not dismiss the value of the assets of those who chose virtual platforms to express their values and creativity.

You may find that what started out as a search for community connections might also identify specific strategies to implement any eventual projects. People who face daily challenges have unique insights into how those challenges might be overcome. Many associations came into being for the sole purpose of mutual benefit.

Read the first section on Asset-Focused Leadership here.

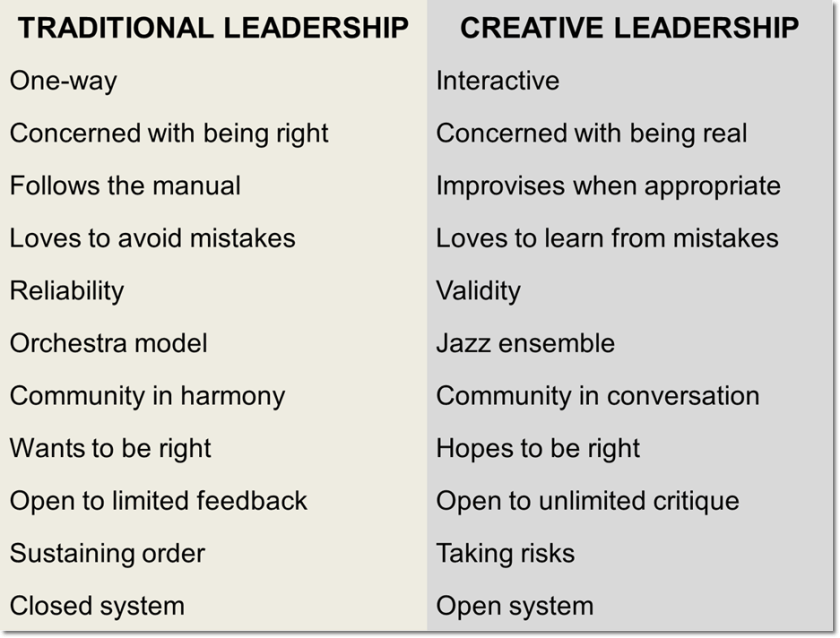

table: John Maeda and Becky Bermont/Redesigning Leadership

table: John Maeda and Becky Bermont/Redesigning Leadership