“The function of leadership is to produce more leaders, not more followers.”

– Ralph Nader

The leadership industry overstates the importance of leaders. They have to; that’s where the money is. The stubborn persistence of positional leadership exists to a great degree, to perpetuate a dualistic notion that some people are better, or more worthy than others. Those with the “leader” moniker assume entitlement. In this model, leaders exist on some higher plane, and followers are considered subordinates. This is all part of a facade that equilibrium and stability are present, and that is supposed to be comforting, I guess.

The world is not simply made up of leaders and followers. Attributes generally attributed to leaders, such as critical thinking, creativity, empathy, and diplomacy, are not solely leadership traits. They are the things that make us human — all of us, “leaders” and “followers.” In most human endeavors, work, commitment, and inspiration by followers dwarfs the contributions of leaders.

When you see evidence that positive change has occurred anywhere in the world, it is usually the result of people who might usually be identified as followers, locking arms with other passionate people, and collaboratively making that change happen. You can’t put “followers” in a box.

In a 2007 article in the Harvard Business Review, Barbara Kellerman suggested a new typology for looking at followers. She categorizes followers based to a certain degree, on how they act in ways that demonstrate “leadership” abilities. Kellerman’s followers are divided into five groups: isolates, bystanders, participants, activists, and diehards. When you get beyond the isolates and the bystanders, you find people who are engaged to varying degrees, in activities that look a lot like what I think of as leadership. These people still strongly support their leaders, but at the same time they aren’t sitting around waiting for marching orders to come down from the next level on an org chart.

Jeffrey Nielsen’s 2004 book, The Myth of Leadership, says that the traditional notion of leaders and followers creates a rank-based culture, with the following assumptions:

According to Nielsen, the implications of the peer principle require that the following values be recognized, respected, and implemented:

According to Nielsen, the implications of the peer principle require that the following values be recognized, respected, and implemented:

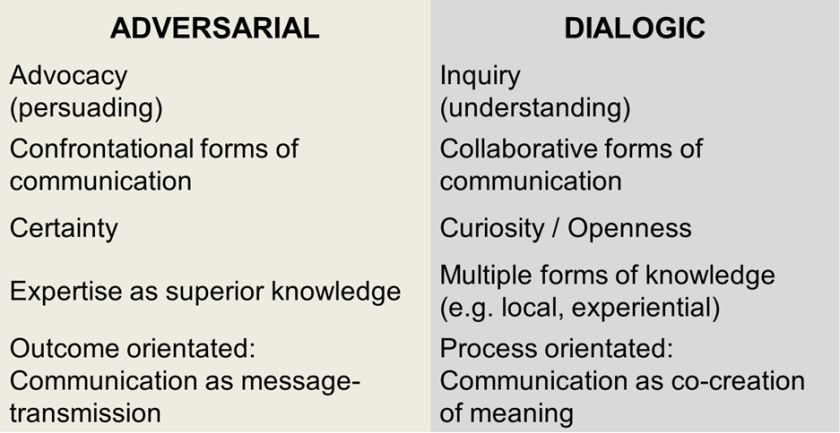

- Openness with information-as opposed to the secrecy allowed and considered legitimate with leaders and leadership.

- Transparency in the decision-making process, which requires greater participation of all affected parties-as opposed to the top-down and behind closed door decision-making allowed and considered legitimate with leaders and leadership.

- Cooperation and sharing of management roles and responsibilities, which requires the exercise of power-in-common-as opposed to the command and control nature of the exercise of power-over allowed and considered legitimate with leaders and leadership.

- Commitment to peer deliberation as the legitimate exercise of authority-as opposed to the rank-based exercise of coercive, manipulative, or even persuasive authority allowed and considered legitimate with leaders and leadership.

“Most of what we call management consists of making it difficult for people to get their work done.”

– Peter Drucker

The myth of leaders versus followers is closely related to the concepts we examined in, Leaders Versus Managers. The idea of maintaining strict control by keeping those around you on a “short leash” works well for cult leaders and dictators, but not for grassroots social change organizing.

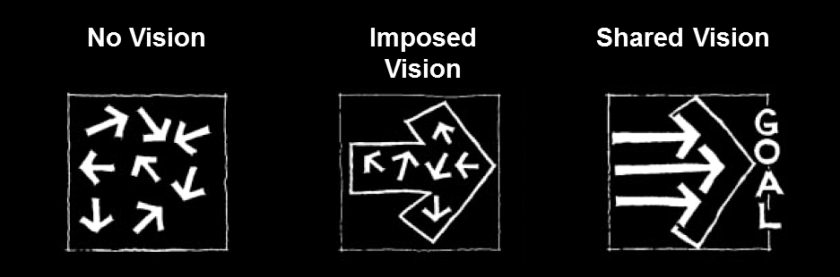

The idea of not equating leadership and control is also a primary difference between leading for change, and leading an organization, be it a business, an NGO, or anything else set up to be an institution. You don’t want people to follow you; you want them to follow a common vision for a better future.